When talking about 20th-century literature, the name Herman Wouk is always mentioned among those who successfully combined the epic sweep of history with individual human destiny. He wrote well into old age, living for over 100 years and remaining an example of tireless creative energy. Read on for the story of this prominent American Jewish writer’s success on bronxski.com.

Through Books and the Ocean

Herman Wouk was born in the Bronx on May 27, 1915, to a family of Jewish immigrants from Belarus. His father, Abraham, started as a laundry worker and later became successful in his own business, while his mother, Esther, instilled a love for books in her children. In their apartment, literature was everywhere. The boy discovered Mark Twain from a set of books bought from a traveling salesman, listened to his father read Sholem Aleichem, and gradually learned to blend humor and seriousness in his writing. His grandfather introduced young Herman to Hebrew and rabbinic texts, so from childhood, he had a dual heritage—American and Jewish.

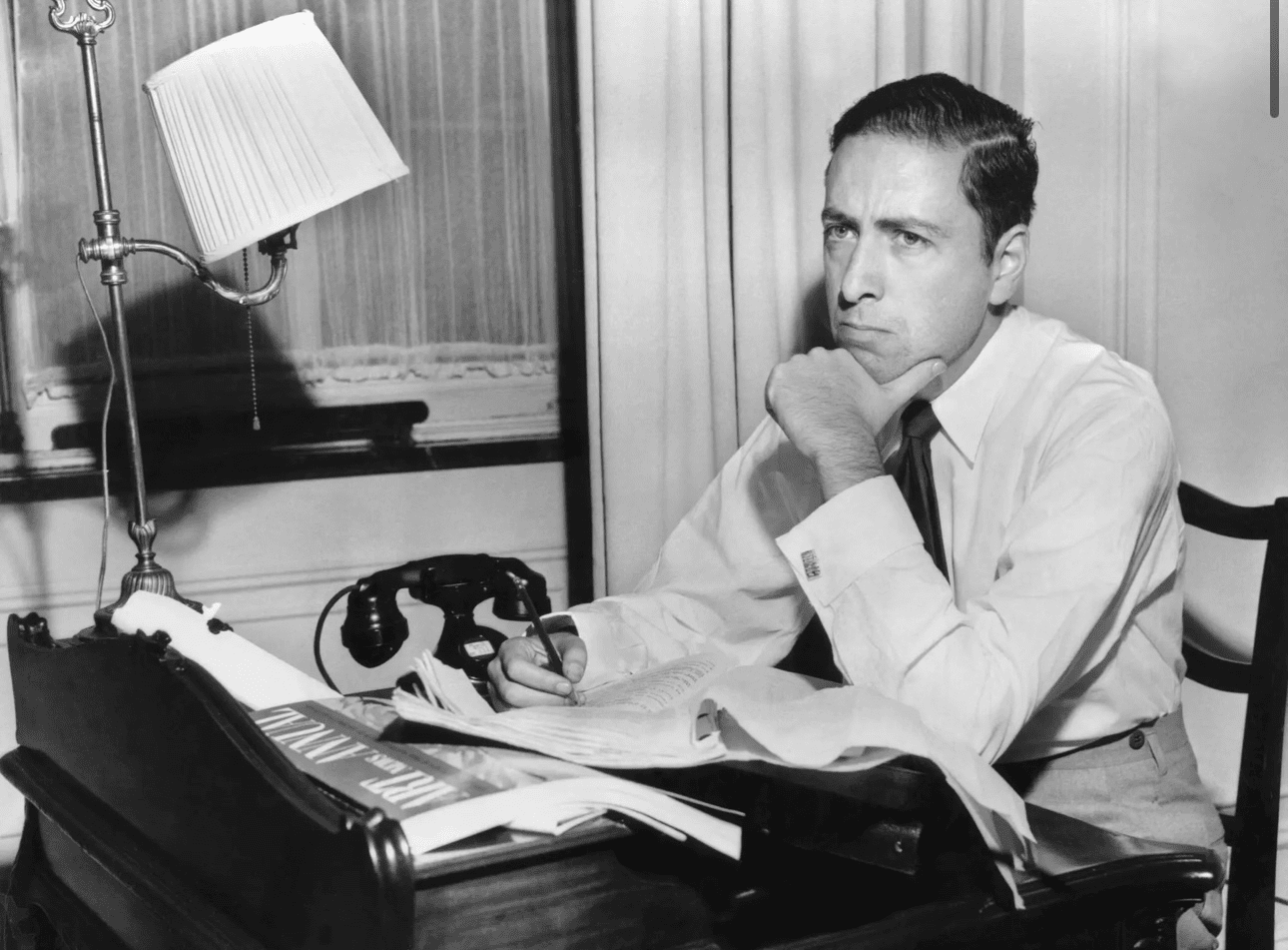

During his school years, Herman often faced ridicule for being “bookish,” but books became his sanctuary. After attending the prestigious Townsend Harris High School, he enrolled at Columbia University. There, he edited the student humor magazine and attended lectures by philosopher Irwin Edman. In 1934, at just twenty years old, Herman earned his degree and plunged into a career as a radio scriptwriter. Within two years, Wouk was writing for the famous comedian Fred Allen, who taught him the art of simplicity and wit.

But his media success did not bring him inner satisfaction. After a period of temporarily abandoning religious practice, he felt an emptiness and later returned to Judaism. Even while moving between the Virgin Islands, Washington, and California, Herman always organized small groups for prayer and Hebrew study.

The turning point in the future writer’s life came with the start of World War II. After Pearl Harbor, Wouk enlisted in the U.S. Navy and became an officer aboard destroyer-minesweepers in the Pacific Ocean. He went through eight amphibious landings, earned battle stars, and at the same time began writing his first novel. On the ship’s deck, amidst the sound of waves and the threat of combat, the manuscript for “Aurora Dawn”was born. Wouk sent fragments to an old professor from Columbia, who helped connect the young officer with an editor. That’s how literature entered his life for good.

Wouk’s first publications—a short play, “The Man in the Cape,” in 1941, and his novel, “Aurora Dawn,” in 1947—marked the beginning of a great creative path. His experience at sea, combined with a childhood love for books, eventually transformed Herman Wouk into one of the most notable American writers of the 20th century.

The Novel That Made Wouk’s Name Immortal

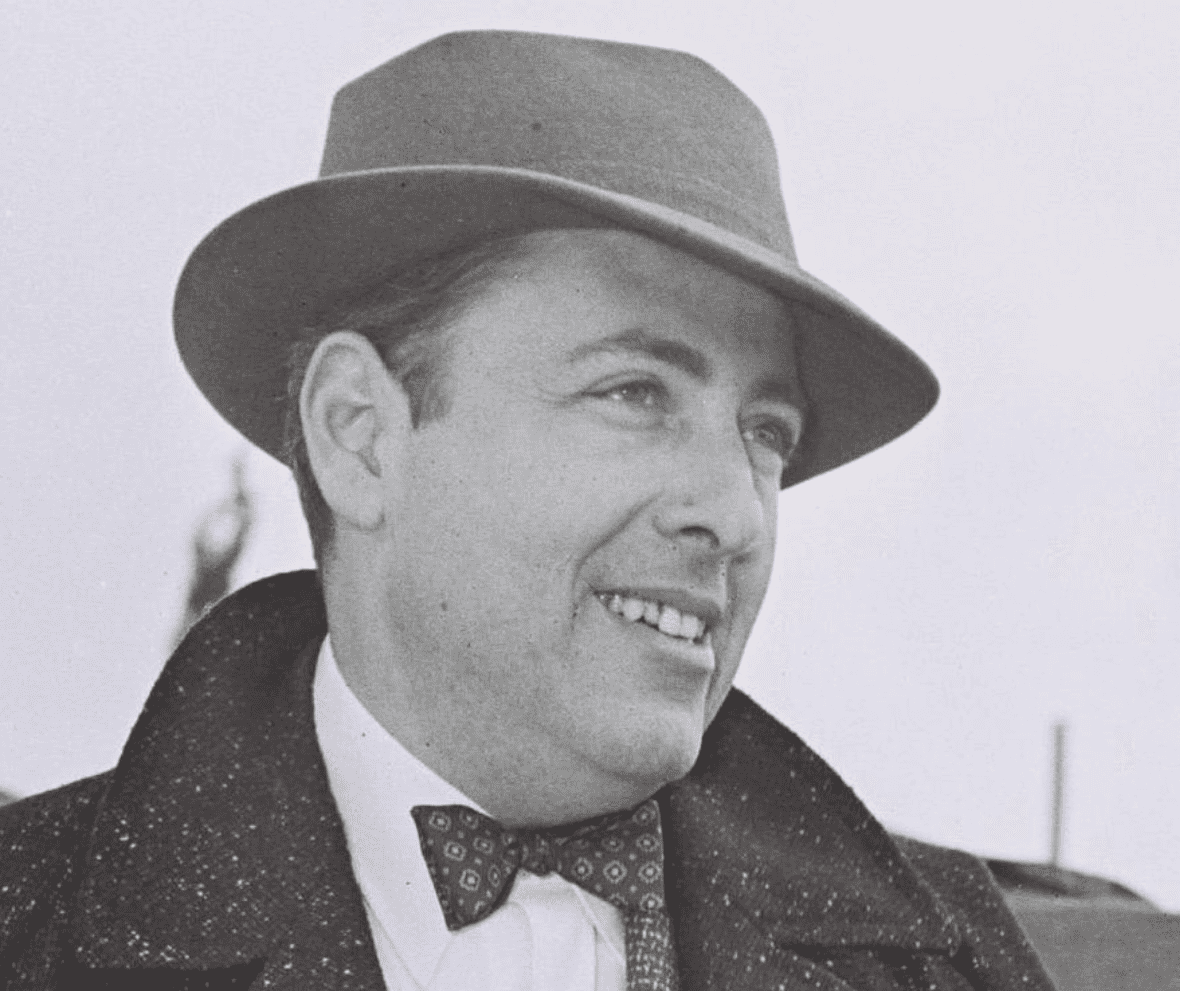

From his naval service, intense combat missions, and reflections on human weakness, Herman Wouk created a work that became part of the canon of world literature. In 1951, his novel “The Caine Mutiny” was published—a drama about officers of an old minesweeper who are forced to challenge their own commander. The character of Captain Queeg, unpredictable, eccentric, and at the same time tragic, was forever etched into American culture.

The book was a huge success and earned Wouk the Pulitzer Prize the following year. In 1954, the story came to life on the big screen. Humphrey Bogart starred in the film, giving his Queeg a nervous intensity and an unforgettable voice. That same year, Wouk himself adapted the novel for Broadway, and the play, “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” gained no less acclaim.

The plot itself is simple but full of depth. Young recruit Willie Keith chooses to serve in the Navy, believing it to be an easier option than the Army. However, aboard the Caine, he finds not comfort but a harsh school of life. A series of strange commanders, routine missions, and finally—an encounter with Captain Queeg, whose eccentricities and inconsistency threaten the safety of the crew. The officers rebel against him and are subsequently court-martialed. They are acquitted, but the system does not forget mutineers.

The young man, Keith, who initially sought easy paths, passes through loss, disappointment, and responsibility step by step. In the end, he becomes the captain of the Caine himself and emerges from the war a completely different man—seasoned, adult, and capable of bearing the burden of true maturity.

This novel was more than just a war story. It became an allegory for America’s coming-of-age, a nation that confronted its own weaknesses in the war and emerged from it transformed.

Literary Legacy

Herman Wouk’s work is characterized by thorough research and attention to detail. His novels convey an accurate and profound picture of their chosen era, focusing on moral dilemmas and human kindness. For example, in “Marjorie Morningstar” (1955), the central theme is a woman’s purity and choices in a complex world. Despite not experimenting with literary form, Herman Wouk’s books achieved immense popularity.

A special place in his work is held by the two-volume cycle about World War II—”The Winds of War” (1971) and “War and Remembrance” (1978). Both novels were adapted into miniseries that received acclaim and awards in the 1980s. This war epic spans the stories of two families—U.S. Navy officer Victor “Pug” Henryand Jewish-American scholar Aaron Jastrow. Through their fates, the author shows the war across the globe: from meetings with Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin to the lives of prisoners in Nazi camps. The structure of the novels is often compared to Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” as they combine large-scale battles with personal dramas.

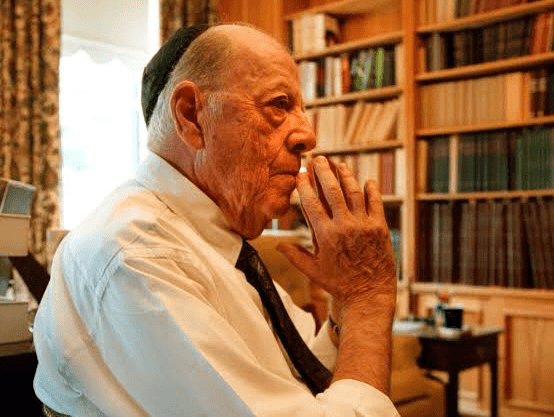

In his later years, Wouk turned to other topics: in the novel “A Hole in Texas” (2004), he used the story of a derailed supercollider project, and his last book, “The Lawmaker” (2012), was a satire on the political world. In 2015, the writer published his memoirs, “Sailor and Fiddler,” in which he summarized his life and creative career.

Patriotism, Religion, and Female Characters in Wouk’s Prose

Herman Wouk was an Orthodox Jew and one of the first writers to bring Judaism into the American mainstream. He believed in the U.S. as a country of salvation for a world engulfed in war and emphasized the great role of the army and, in particular, the navy in achieving victory.

His patriotic vision differed from the pessimism of other 20th-century writers. Wouk did not seek to portray war only as chaos and destruction but saw in it an organized struggle for great goals.

Special attention should be paid to Herman Wouk’s attitude toward women. In his novels, they are portrayed as bold, strong, and independent. At the same time, the writer adhered to traditional views on female chastity and marital fidelity, which seemed archaic even in the 1970s. The virtuous women in his works are devoted mothers and wives, while the unfaithful female characters are almost always doomed to condemnation.

For Wouk, the main thing was to show the strength of America and its mission in the world. His novels did not seek to expose the dark sides of history; instead, they affirmed faith in the country, duty, and human kindness. This is what made him one of the most distinguished American writers of military fiction and the voice of an entire generation.

The Love of His Life and Recognition

During his service in the Navy, while Herman Wouk’s ship was undergoing repairs in California, he met the woman who would become his greatest support for the rest of his life. Her name was Betty Sarah Brown, a graduate of the University of Southern California and a civilian Navy employee. In 1945, the couple married. Together, they raised three sons, although their family happiness was overshadowed by tragedy: their eldest son, Abraham, died in childhood. The couple later had two other sons—Nathaniel and Joseph. Betty was not only his wife but also became Wouk’s literary agent, supporting his career until her own death in 2011.

Wouk’s novels are distinguished by a wealth of detail and historical accuracy—the result of painstaking research, much of which the writer conducted at the Library of Congress. He had a special friendship with this institution: in the late 1990s, he donated his manuscripts, including those for “The Winds of War” and “War and Remembrance,” to them.

The Library of Congress was the very place where Wouk’s life’s work was celebrated. He was the first recipient of the Fiction Award—an honor that recognized his contribution to American culture.

“The Library of Congress occupies a unique place in America. And for me personally, as a collector and keeper of our country’s great intellectual and creative heritage, it is a special honor to receive this award,” Wouk said. “Thank you for recognizing my life’s work.”

Herman Wouk lived for more than a hundred years, maintaining a sharp mind and a capacity for work until his final days. On May 17, 2019, he passed away at the age of 103, leaving behind a legacy that continues to speak to readers with the power of history and the wisdom of experience.