This author is considered a chronicler of American anxiety, a writer who transformed the fears and paranoia of an era into literature that makes you think about the meaning of existence. Read on to discover the success story of this simple kid from the Bronx who achieved global fame on bronxski.com.

The Hard Start

Don DeLillo was born on November 20, 1936, in the Bronx, to a family of Italian immigrants from the Abruzzo mountains. His childhood was immersed in a bilingual world: a dialect of Italian was spoken at home, while English, mixed with local slang, filled the streets. His father worked for an insurance company, his mother tried to understand her new country, and Don grew up among streets where cultures and languages intertwined. From an early age, he felt like a witness to the clash of old and new America.

He studied at Fordham University in the Bronx, where he focused on religion and philosophy. However, he had no illusions about a career in academia or politics. He failed the medical exam for military service, being too young for Korea and too old for Vietnam. After graduation, Don took a job as a copywriter at the famous agency Ogilvy & Mather, working on advertisements and fulfilling his parents’ dream of seeing their son in a suit and tie. Yet, DeLillo found neither peace nor satisfaction in this work. Since childhood, he had a dream of becoming a writer, but for many years, he hesitated and constantly put his manuscripts aside, despite numerous attempts to write something.

It wasn’t until he was 35 years old, after much doubt, that his first novel, “Americana,” was published in 1971—the story of a TV network executive searching for the “real” America. DeLillo confessed:

“I was a very slow starter. I lacked the discipline for the huge commitments you have to make. Even when I had a full day to write, and sometimes a full week, it finally took me forever to write my first novel. I didn’t have much expectation of getting it published because it was a kind of a mess. It was only when I discovered I was writing things I didn’t know I knew that I said, ‘Now I’m a writer.'”

DeLillo’s path into literature was marked by the influence of major events. The assassination of John F. Kennedy left a particularly strong impression. The sense of uncertainty, conspiracy, and anxiety that gripped the country afterward became the basis for many of his themes.

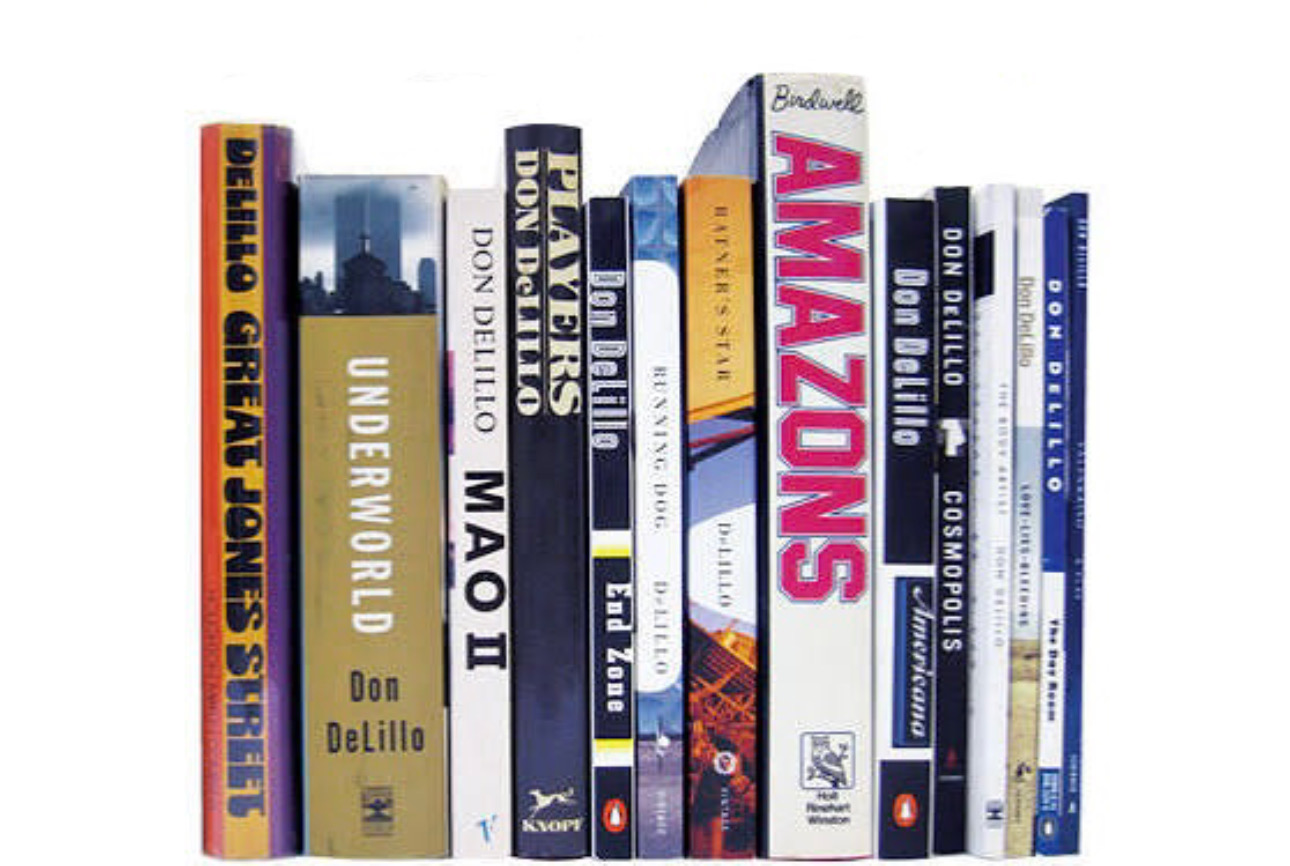

His early works, such as “End Zone” (1972), “Great Jones Street” (1973), and “Ratner’s Star” (1976), gradually earned him critical acclaim.

The Making of a Writer

After his initial attempts to find his own voice, Don DeLillo entered a new phase in the mid-1970s. Beginning with the novel “Players” (1977), his worldview grew darker, and his characters became increasingly daring in their destructiveness and helplessness. Critics noted that it was difficult to sympathize with these characters, but DeLillo’s language itself—elliptical, fragmented, filled with a sense of an elusive subtext—was irresistibly compelling.

This was followed by the thrillers “Running Dog” (1978) and “The Names” (1982), parts of which are set in Greece. But his true breakthrough was the 1985 novel “White Noise,” which earned DeLillo the National Book Award. It’s the story of a professor of Hitler studies whose life is disrupted by a toxic cloud, which changes his very sense of reality. Here, the author tackles the theme of the fear of death—a topic that is both universal and incredibly modern.

In the late 1980s, Don DeLillo bravely engaged with history. In the novel “Libra” (1988), he creates a fictional portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald, and in “Mao II” (1991), he explores how political violence changes the role of the writer in the world.

His most significant recognition came with the epic novel “Underworld” (1997)—a sweeping story about America during the Cold War era.

In the 21st century, DeLillo hasn’t lost his experimental spirit. “The Body Artist” (2001) tells of a widow who experiences a mystical event. In “Cosmopolis” (2003), the action takes place in a billionaire’s limousine as it travels through Manhattan. Following the September 11 attacks, Don DeLillo wrote “Falling Man” (2007), which explores the trauma of survival. In “Point Omega” (2010), he reflects on the nature of time, and in “Zero K” (2016), on cryonics and the search for immortality. His late novel, “The Silence” (2020), transports the reader to a world of global catastrophe, where a few people try to make sense of a new reality during a Super Bowl party.

In addition to his novels, DeLillo has written plays and screenplays, as well as a collection of short stories, “The Angel Esmeralda” (2011), which brought together nine stories.

Art and Terror: The Author’s Terrifying and Beautiful Style

In his works, Don DeLillo delves into the dark depths of American culture: from the broken David Bell(Americana) to the obsessed Bill Gray (Mao II), from the deranged Lee Harvey Oswald (Libra) to the suicidal Eric Packer (Cosmopolis). Even in “White Noise,” professor Jack, who teaches Hitler studies, reflects with bitter humor on death and mass murder.

It’s said that on DeLillo’s writing desk, there were always two folders: “Art” and “Terror.” He explained this symbolic division in Mao II:

“I used to think that a writer could change the inner life of a culture. Now that territory is occupied by bomb makers and gunmen.”

It’s no surprise that his vision is often called paranoid—he connects all the elements of modern society into a single, anxious, but coherent picture.

Critics and readers felt that DeLillo had almost prophetic abilities. In Mao II, some saw a premonition of the war on terror. The cover of Underworld supposedly echoes the image of the planes that would later crash into the Twin Towers. And White Noise resonated with the anthrax scares of 2001.

DeLillo admits that he never plans his novels. He works with random notes on scraps of paper that he always carries with him. He then returns to them weeks or months later.

“I never made an outline for any novel I wrote,” he says.

DeLillo’s work shows that he always allows art to find its own way, to respond to the time and place he lives in. For him, writing is not about finished plots and neat epilogues but about penetrating the essence of modern America, where art and terror are intertwined in a complex dance.

DeLillo’s prose sounded almost musical. The rhythms, cadences, repetitions, and lyrical passages pushed the plot forward as if he were writing a symphony, not a novel. It’s no coincidence that music was at the core of his childhood. For DeLillo, the feeling of an era—how it smelled, sounded, and moved, how its people spoke—was more important than dry facts. He trusted paintings, photographs, and living images more than statistics.

“We live in the past more than we think,” the writer said. “Everyone, looking in the mirror, sees their parents.”

And he knew how to return these voices and images of generations to the reader across the distance of time and memory.

Awards, Recognition, and Place in American Literature

Don DeLillo’s work has been honored with numerous awards: the National Book Award (White Noise, 1985), the PEN/Faulkner Award (Mao II, 1992), the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for achievement in American fiction (2010), and many others. In 1979, he also received a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation.

In 2006, The New York Times conducted a poll of hundreds of writers, critics, and editors to determine the best American novel of the past 25 years. DeLillo’s novel Underworld (1997) came in second place, and White Noise and Libra were also on the list.

DeLillo received special recognition in 2013 when he was awarded the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction at the National Book Festival. This honor celebrates writers who combine artistic excellence, originality of thought, and imagination, and whose works consistently tell the story of the American experience.

The writer himself connected the award to his family history:

“My first thoughts were of my mother and father who came to this country the hard way. In a real sense, the Library of Congress prize is a culmination of their effort and a tribute to their memory.”

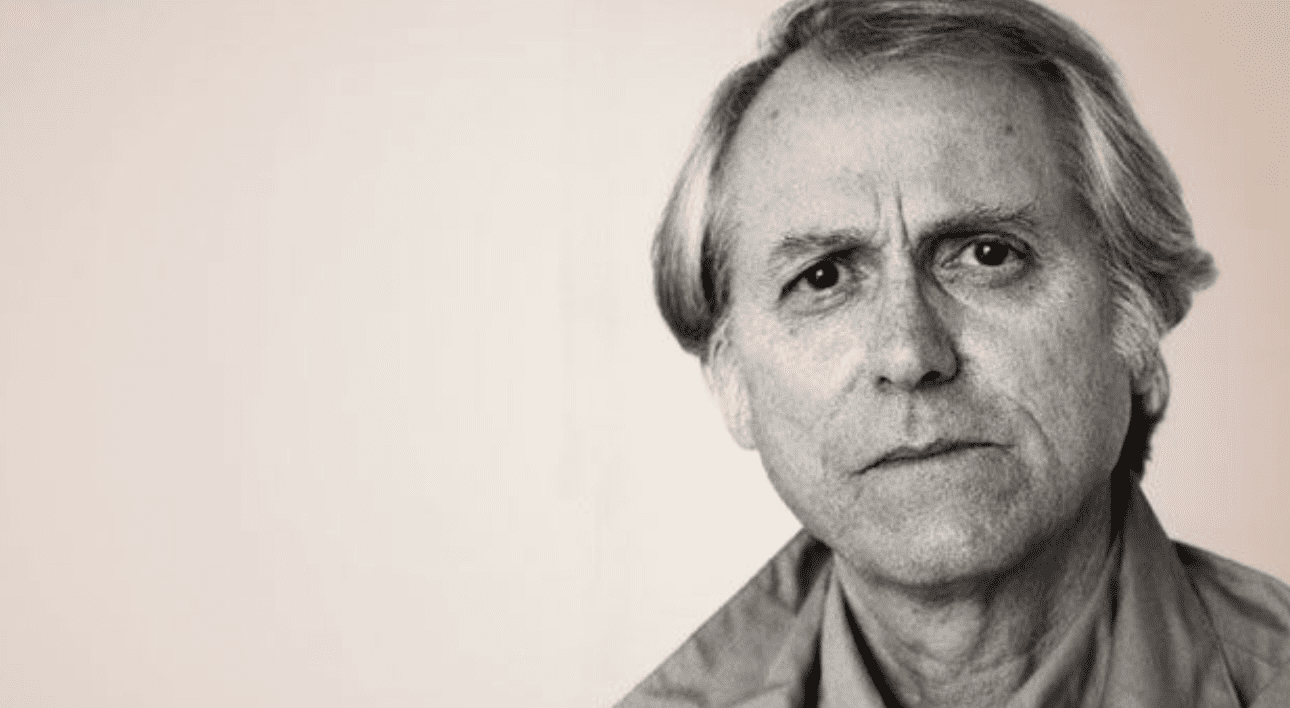

In the twilight of one’s life

In his later years, Don DeLillo lives in Westchester County, New York, with his wife Barbara, but his heart remains in the Bronx—the borough of his childhood. Every year, DeLillo returns to meet with old friends: they have lunch together, laugh, and inevitably turn to baseball—his first love, which he calls his second language. Having grown up with baseball, radio, and trips to Yankee Stadium, Don considers it “a self-evident pleasure.”

Although the writer is often described as a recluse, he rejects this label.

“I’m not a recluse at all. Just private,” DeLillo says.

He admits that aging affects his creative process and that his work has become slower. It took him nearly four years to write his last book, and it’s not even 300 pages long. DeLillo himself recognizes that the world of his novels is a tightly wound machine that is slowly falling apart. Having traveled from the working-class Bronx to fame on Madison Avenue and now to a quiet home in upstate New York, he says:

“I’ve had a very happy life. I was a very happy writer.”

The author remains true to old traditions: he writes his books on a manual typewriter and doesn’t use email. And although the world is changing around him, DeLillo remains a giant of 20th-century literature, even in the age of news and social media.