An ordinary boy from the Bronx, named after Poe, became one of the most influential American novelists of the 20th century. His books masterfully blend history, philosophy, and literary craftsmanship. This incredible story of success is explored further on bronxski.com.

The Gradual Making of a Writer

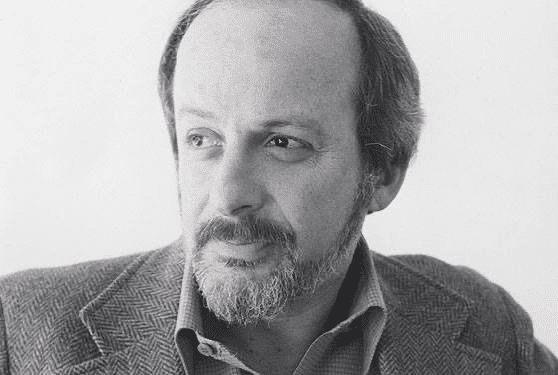

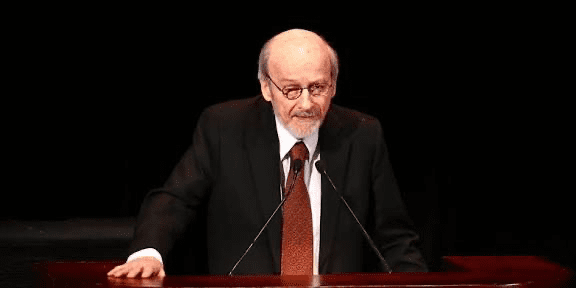

E. L. Doctorow was born on January 6, 1931, in the Bronx to a second-generation family of Jewish immigrants from Russia. His father owned a music shop where classical melodies always played, and his mother instilled in him a love for books. It’s no surprise that the boy was named after Edgar Allan Poe, a writer known for bringing dark and mysterious worlds to life.

The future author’s childhood was spent on the streets of the Bronx, and his first attempts at writing were within the walls of the prestigious Bronx High School of Science. There, among mathematical geniuses, he found his own niche in a literary club and the school magazine, where his work was first published. It was then that young Doctorow realized his path was with words, which had the power to change reality.

He continued his education at Kenyon College in Ohio, where he studied philosophy, acted in student theater productions, and took courses with the renowned poet-critic John Crowe Ransom. It was in college that Doctorow was introduced to the literary discussions that would later profoundly influence his own style.

After graduation, Doctorow entered a graduate program in drama at Columbia University, but his studies were interrupted by military service. He spent two years in West Germany, working in the Army Signal Corps during the Korean War. During this period, Edgar married the writer Helen Setzer, with whom he later raised three children.

Returning to New York, Doctorow worked at Columbia Pictures, reading stacks of screenplays, many of them Westerns. It was then that he conceived the idea for his own novel, with the ironic title “Welcome to Hard Times.” When the book was published in 1960, critics called it “dramatic, tense, and brightly symbolic.”

Edgar then worked as an editor and publisher. At New American Library, he edited texts by Ian Fleming and Ayn Rand, and at Dial Press, he published books by Norman Mailer and James Baldwin. But eventually, Doctorow left his publishing career to focus on his own creative work.

When asked why he became a writer, Edgar answered simply:

“I was a kid who read everything. At some point, I became interested not just in what would happen next but in how to make a story come alive on the page. That’s when I realized I had to write.”

Immersion in a Literary Life

In 1966, Doctorow published his second novel, “Big as Life,” which he later forbade from being reissued. In 1969, he left the publishing business and fully dedicated himself to literature. At the University of California, Irvine, where he was invited as a writer-in-residence, Doctorow completed “The Book of Daniel” in 1971. This work, inspired by the trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, received rave reviews. The Guardian called the novel a masterpiece, and The New York Times ranked the author among the first tier of American writers.

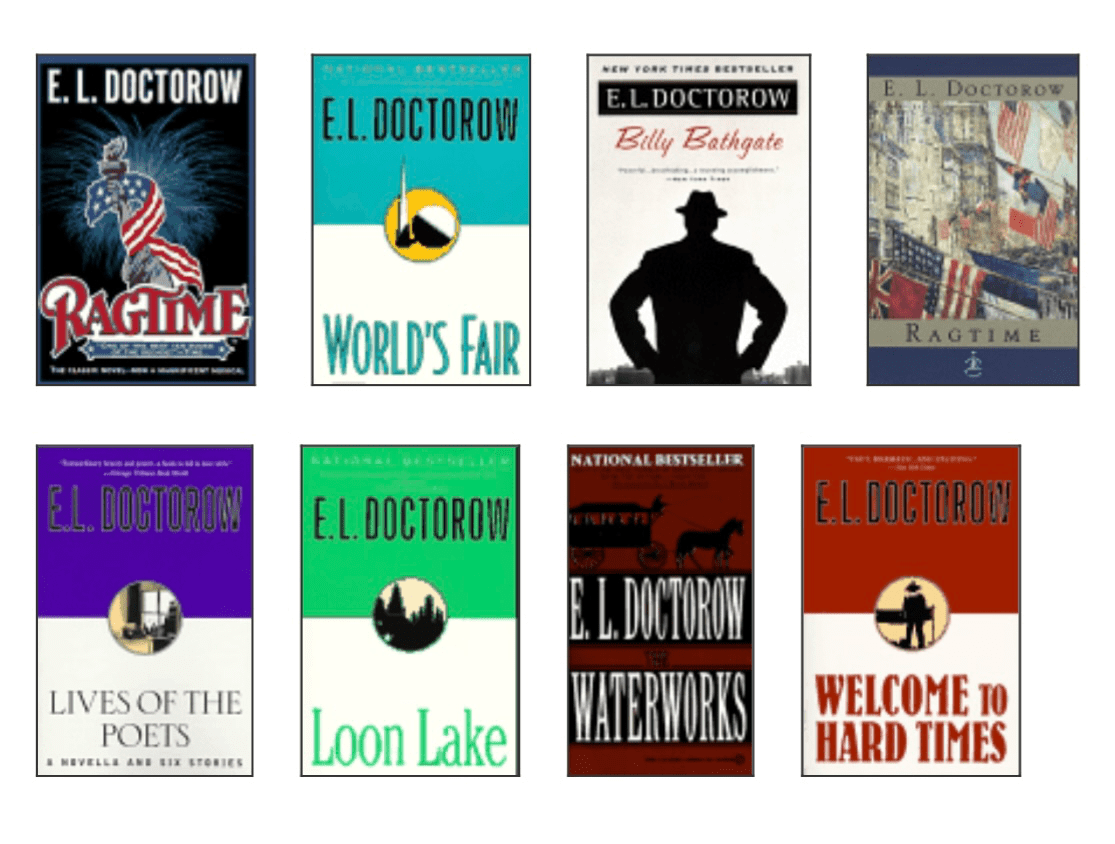

The young author’s next book, “Ragtime,” which he wrote in 1975, brought him worldwide recognition. It was included on Modern Library’s list of the 100 best novels of the 20th century. This work wove together fictional and real figures in a whimsical dance of American history—from Henry Ford to Sigmund Freud, from Carl Jung to J. P. Morgan. This unique style of blending fiction with fact, and irony with epic scale, became the author’s literary signature.

From the 1980s to the 2000s, Doctorow created a series of landmark works, including “Loon Lake” (1980), “World’s Fair” (1985), “Billy Bathgate” (1989), “The Waterworks” (1994), “City of God” (2000), and “The March” (2005). In his 2009 novel “Homer & Langley,” he explored the story of the Collyer brothers, eccentric hermits from Harlem, and his final book was the experimental “Andrew’s Brain,” written in 2014.

Besides novels, Doctorow wrote plays, short stories, and essays. His collections “Lives of the Poets” (1984), “Sweet Land Stories” (2004), “All the Time in the World” (2011), as well as his volumes of essays, “Reporting the Universe” (2003) and “The Creationists” (2006), demonstrate the breadth of his interests — from literature to science.

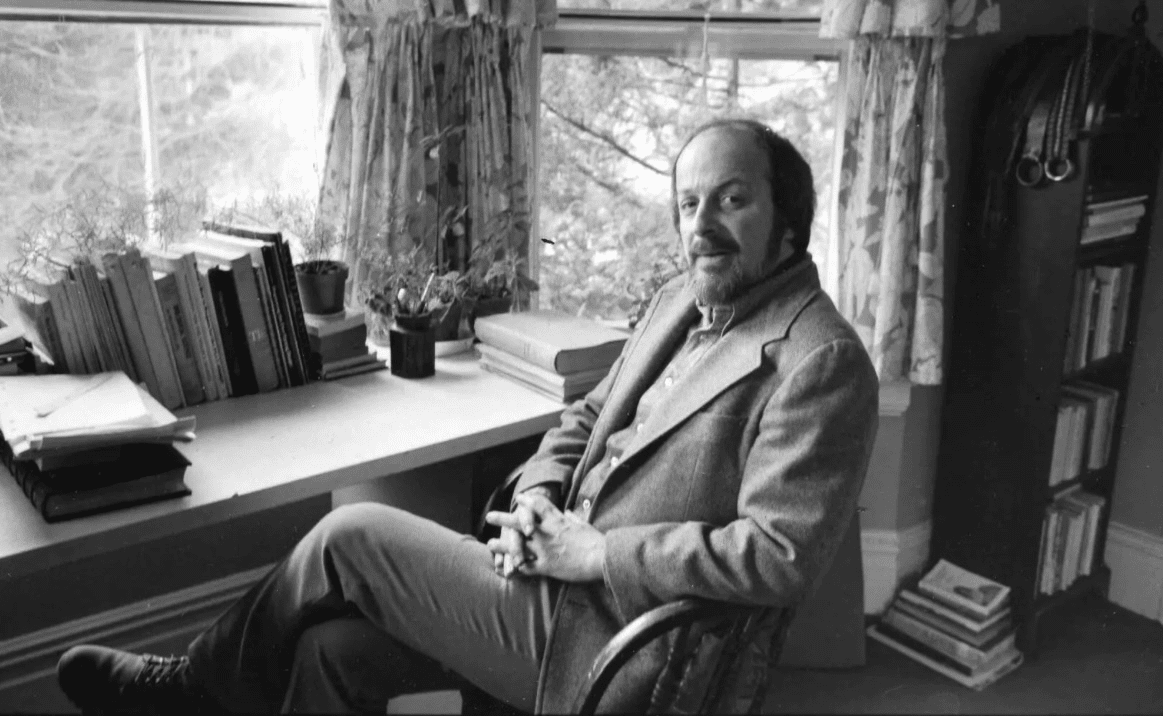

E. L. Doctorow taught at leading universities across the country, from the Yale School of Drama to Princeton, and from 1982, he was a professor of English and American literature at New York University.

A Unique Style

E. L. Doctorow was a master at transforming the past into a living, palpable reality. His novels, based on meticulous research, never felt like “dust from old newspaper archives,” as critic John Brooks noted.

“We tell and retell stories, and those stories illuminate our daily lives. He showed us again and again that our past is our present, and that those who refuse to wrestle with what happened will be doomed to repeat its worst mistakes,” wrote Jay Parini.

Doctorow knew how to take genre forms and use them as mirrors of history.

He did not believe in progress as a linear movement forward and did not accept the absolute nature of historical facts.

“Where myth and history meet is where my novels begin,” he said.

For Edgar, literature was never a document or a political manifesto. Fiction, for him, was a space of intuition, myth, and metaphysics that goes beyond the language of politics. His texts were striking for their innovative structure, the blurring of lines between fact and fiction, and the exploration of themes like war, family ties, identity, alienation, justice, corruption, and human consciousness. He himself confessed:

“I’ve always been a writer who invents. I create books to be lived in. I lived in them while I was writing. Now it’s the reader’s turn.”

Doctorow’s prose sounded almost musical. The rhythms, cadences, repetitions, and lyrical passages drove the plot forward as if he were writing a symphony, not a novel. It’s no wonder music was at the heart of his childhood. For Doctorow, the feeling of an era—how it smelled, sounded, moved, and how its people spoke—was more important than dry facts. He trusted pictures, photographs, and living images more than statistics.

“We live in the past more than we think,” the writer said. “Everyone, looking in the mirror, sees their parents.”

And he knew how to return these voices and images of generations to the reader across the distance of time and memory.

Awards and Legacy

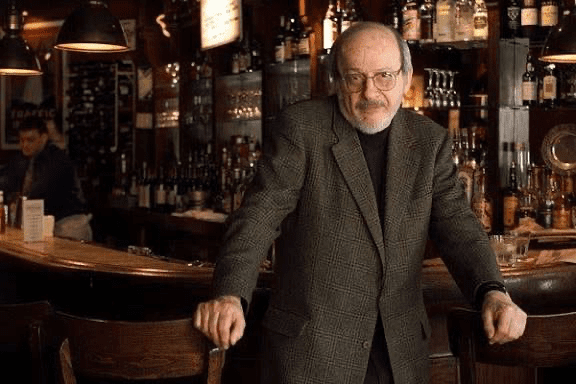

E. L. Doctorow holds an honored place among the most distinguished American writers, as his creative career spanned over half a century. During that time, he won a great number of awards and honors. These include the National Humanities Medal (1998), induction into the New York Writers Hall of Fame (2012), the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for achievement in American fiction (2012), the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (2013), and more. In 2014, he also received the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

This author’s body of work was repeatedly recognized with prestigious awards. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award three times (for Ragtime, Billy Bathgate, and The March), the National Book Award for World’s Fair (1986), and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Billy Bathgate (1990) and The March (2006). His name was first a nominee for the National Book Award back in 1972, for The Book of Daniel.

Doctorow was published in influential literary magazines such as the New Yorker, Kenyon Review, Atlantic, Paris Review, and Gentleman’s Quarterly. He always attracted the attention of critics and readers, was a Guggenheim Foundation fellow, and received the William Dean Howells Medal, the Edith Wharton Citation of Merit, the Chicago Tribune literary prize, and other honors.

“E. L. Doctorow is our own Charles Dickens, who embodies a distinctly American space and time and delivers our countless voices,” said Librarian of Congress James Billington during an awards ceremony. “Every book is a vibrant canvas filled with color and drama. In each, he describes a completely different world.”

Beyond the literary scene, Doctorow also showed a civic commitment. He was a member of the pro-Israel group “Writers and Artists for Peace in the Middle East” and in 1984 signed an open letter against the sale of German weapons to Saudi Arabia.

E. L. Doctorow’s approach to writing was defined by the belief that history in a novel must be subordinate to the author’s imagination. For him, fiction had an autonomous, even primary power, and historical facts became merely material for artistic interpretation.

On July 21, 2015, the great writer died at the age of 84 in Manhattan from lung cancer. He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx—where his life and work came full circle.